Go To: Commodore 64

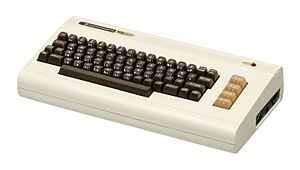

The VIC-20 (in Germany, VC-20;[3] in Japan, VIC-1001) is an 8-bit home computer that was sold by Commodore Business Machines. The VIC-20 was announced in 1980,[4] roughly three years after Commodore’s first personal computer, the PET. The VIC-20 was the first computer of any description to sell one million units.[5] The VIC-20 has been described as “one of the first anti-spectatorial, non-esoteric computers by design…no longer relegated to hobbyist/enthusiasts or those with money, the computer Commodore developed was the computer of the future.”

History

Origin and marketing

The VIC-20 was intended to be more economical than the PET computer. It was equipped with 5 KB of static RAM and used the same MOS 6502 CPU as the PET. The VIC-20’s video chip, the MOS Technology VIC, was a general-purpose color video chip designed by Al Charpentier in 1977 and intended for use in inexpensive display terminals and game consoles, but Commodore could not find a market for the chip.

As the Apple II gained momentum with the advent of VisiCalc in 1979, Jack Tramiel wanted a product that would compete in the same segment, to be presented at the January 1980 CES. For this reason Chuck Peddle and Bill Seiler started to design a computer named TOI (The Other Intellect). The TOI computer failed to materialize, mostly because it required an 80-column character display which in turn required the MOS Technology 6564 chip. However, the chip could not be used in the TOI since it required very expensive static RAM to operate fast enough.

In the meantime, freshman engineer Robert Yannes at MOS Technology (then a part of Commodore) had designed a computer in his home dubbed the MicroPET and finished a prototype with some help from Al Charpentier and Charles Winterble. With the TOI unfinished, when Jack Tramiel was shown the MicroPET prototype, he immediately said he wanted it to be finished and ordered it to be mass-produced following a limited demonstration at the CES.

As the new decade began, the price of computer hardware was dropping and Tramiel saw an emerging market for low-price computers that could be sold at retail stores to relative novices rather than professionals or people with an electronics or programming background. The personal computer market up to this point had sold primarily through mail order or authorized dealers, the sole exception being Radio Shack, who had their own stores as a distribution network. Radio Shack had been achieving considerable success with the TRS-80 Model I, a relatively low-cost machine that was widely sold to novices and in 1980 released the Color Computer, which was aimed at the home and educational markets, utilized ROM cartridges for software, and connected to an ordinary TV set.

The prototype produced by Yannes had very few of the features required for a real computer, so Robert Russell at Commodore headquarters had to coordinate and finish large parts of the design under the codename Vixen. The parts contributed by Russell included a port of the operating system (kernel and BASIC interpreter) taken from John Feagans design for the Commodore PET, a character set with the characteristic PETSCII, an Atari 2600-compatible joystick interface, and a ROM cartridge port. The serial IEEE 488-derivative CBM-488 interface[7] was designed by Glen Stark. It served several purposes, including costing substantially less than the IEE-488 interface on the PET, using smaller cables and connectors that allowed for a more compact case design, and also complying with newly-imposed FCC regulations on RFI emissions by home electronics (the PET was certified as Class B office equipment which had less stringent RFI requirements). Some features, like the memory add-in board, were designed by Bill Seiler.[citation needed] Altogether, the VIC 20 development team consisted of five people, who referred to themselves as the VIC Commandos.[8] According to one of the development team, Neil Harris, “[W]e couldn’t get any cooperation from the rest of the company who thought we were jokers because we were working late, about an hour after everyone else had left the building. We’d swipe whatever equipment we needed to get our jobs done. There was no other way to get the work done! […] they’d discover it was missing and they would just order more stuff from the warehouse, so everybody had what they needed to do their work.”[8] At the time, Commodore had a glut of 1 kbit×4 SRAM chips, so Tramiel decided that these should be used in the new computer. The end result was arguably closer to the PET or TOI computers than to Yannes’ prototype, albeit with a 22-column VIC chip instead of the custom chips designed for the more ambitious computers. As the amount of memory on the VIC-20’s system board was very small even for 1981 standards, the design team could get away with using more expensive SRAM due to its lower power consumption, heat output, and less supporting circuitry. The original Revision A system board found in all silver-label VIC-20s used 2114 SRAMs and due to their tiny size (only 512 bytes per chip), ten of them were required to reach 5 KB of system RAM. The Revision B system board, found in rainbow logo VIC-20s (see below) switched to larger 2048-byte SRAMs which reduced the memory count to five chips: 2× 2048-byte chips + 3× 2114 (the 1024 × 4 bits) chips.

While newer PETs had the upgraded BASIC 4.0, which had disk commands and improved garbage collection, the VIC-20 reverted to the 8 KB BASIC 2.0 used on earlier PETs as part of another of the design team’s goals, which was limiting the system ROMs to only 20 KB. Since Commodore’s BASIC had been designed for the PET which had only limited audiovisual capabilities, there were no dedicated sound or graphics features, thus VIC-20 programmers had to use large numbers of POKE and PEEK statements for this. This was in contrast to the computer’s main competitors, the Atari 400 and TRS-80 Color Computer, both of which had full-featured BASICs with support for the machines’ sound and graphics hardware. Supplying a more limited BASIC in the VIC-20 would keep the price low and the user could purchase a BASIC extender separately if he desired sound or graphics commands.

While the TRS-80 Color Computer and Atari 400 had only RF video output, the VIC-20 instead had composite output, which provided a sharper, cleaner picture if a dedicated monitor was used. An external RF modulator was necessary to use the computer with a TV set, and had not been included internally so as to comply with FCC regulations (Commodore lobbied for and succeeded in getting them relaxed slightly by 1982, so the C64 had an RF modulator built in).

VIC-20s went through several variations in their three and a half years of production. First-year models (1981) had a PET-style keyboard with a blocky font while most VIC-20s made during 1982 had a slightly different keyboard also shared with early C64s. The rainbow logo VIC-20 was introduced in early 1983 and has the newer C64 keyboard with gray function keys and the Revision B motherboard. It has a similar power supply to the C64 PSU, although the amperage is slightly lower. A C64 “black brick” PSU is compatible with Revision B VIC-20s; however, the VIC’s PSU is not recommended on a C64 if any external devices such as cartridges or user port accessories are installed as it will overdraw the available power. Older Revision A VIC-20s cannot use a C64 PSU or vice versa as their power requirement is too high.

The VIC-1001 was the Japanese version of the VIC-20. It featured Japanese-language characters in the ROM[9] and on the front of the keys.

In April 1980, at a meeting of general managers outside London, Jack Tramiel declared that he wanted a low-cost color computer. When most of the GMs argued against it, he said: “The Japanese are coming, so we will become the Japanese.” This was in keeping with Tramiel’s philosophy which was to make “computers for the masses, not the classes”. The concept was championed at the meeting by Michael Tomczyk, newly hired marketing strategist and assistant to the president, Tony Tokai, General Manager of Commodore-Japan, and Kit Spencer, the UK’s top marketing executive.[citation needed] Then, the project was given to Commodore Japan; an engineering team led by Yash Terakura created the VIC-1001 for the Japanese market. The VIC-20 was marketed in Japan as VIC-1001 before VIC-20 was introduced to the US.

The Commodore 1530 C2N-B Datasette provided inexpensive external storage for the VIC-20

When they returned to California from that meeting, Tomczyk wrote a 30-page memo detailing recommendations for the new computer, and presented it to Tramiel. Recommendations included programmable function keys (inspired by competing Japanese computers),[10] full-size typewriter-style keys, and built-in RS-232. Tomczyk insisted on “user-friendliness” as the prime directive for the new computer, to engineer Yash Terakura (who was also a friend),[10] and proposed a retail price of US$299.95. He recruited a marketing team and a small group of computer enthusiasts, and worked closely with colleagues in the UK and Japan to create colorful packaging, user manuals, and the first wave of software programs (mostly games and home applications).

Scott Adams was contracted to provide a series of text adventure games. With help from a Commodore engineer who came to Longwood, Florida to assist in the effort, five of Adams’s Adventure International game series were ported to the VIC. They got around the limited memory of VIC-20 by having the 16 KB games reside in a ROM cartridge instead of being loaded into main memory via cassette as they were on the TRS-80 and other machines. The first production run of the five cartridges generated over $1,500,000 in sales for Commodore.[citation needed]

While the PET was sold through authorized dealers, the VIC-20 primarily sold at retail—especially discount and toy stores, where it could compete more directly with game consoles. It was the first computer to be sold in K-Mart. Commodore took out advertisements featuring actor William Shatner (of Star Trek fame) as its spokesman, asking: “Why buy just a video game?” and describing it as “The Wonder Computer of the 1980s”. Television personality Henry Morgan (best known as a panelist on the TV game show I’ve Got a Secret) became the commentator in a series of Commodore product ads.

The VIC-20 had 5 KB of RAM, of which only 3.5 KB remained available on startup (exactly 3583 bytes). This is roughly equivalent to the words and spaces on one sheet of typing paper, meeting a design goal of the machine. The computer was expandable up to 40 KB with an add-on memory cartridge (a maximum of 27.5 KB was usable for BASIC).

The “20” in the computer’s name was widely assumed to refer to the text width of the screen (although in fact the VIC-20 has 22-column text, not 20) or that it referred to the combined size of the system ROMs (8 KB BASIC+8 KB KERNAL+4 KB character ROM).[citation needed] Bob Yannes claimed that “20” meant nothing in particular and “We simply picked ’20’ because it seemed like a friendly number and the computer’s marketing slogan was ‘The Friendly Computer’. I felt it balanced things out a bit since ‘Vic’ sounded like the name of a truck driver.”

In 1981, Tomczyk contracted with an outside engineering group to develop a direct-connect modem-on-a-cartridge (the VICModem), which at US$99 became the first modem priced under US$100. The VICModem was also the first modem to sell over 1 million units. VICModem was packaged with US$197.50 worth of free telecomputing services from The Source, CompuServe and Dow Jones. Tomczyk also created a SIG called the Commodore Information Network to enable users to exchange information and take some of the pressure off of Customer Support inquiries, which were straining Commodore’s lean organization. In 1982, this network accounted for the largest traffic on CompuServe.[citation needed]

Decline

The VIC-20 was the best-selling computer of 1982, with 800,000 machines sold. One million units had been sold by the end of the first full year of production; at one point, 9,000 units a day were being produced.[citation needed] That summer, Commodore unveiled the Commodore 64, a more advanced machine with 64 KB of RAM and considerably improved sound and graphics capabilities. Sales of the C64 were slow at first due to reliability problems and lack of software. But by the middle of 1983, sales of the C64 took off resulting in plunging sales for the VIC-20. In order to try and staunch the sales decline, by mid-1983 the computer had become widely available for under $90.[11] As sales of the computer continued to decline, the VIC-20 was quietly discontinued in January 1985.[12] Perhaps the last new commercially available VIC-20 peripheral was the VIC-Talker, a speech synthesizer; Ahoy! in January 1986 wrote when discussing it, “Believe it or not, a new VIC accessory … We were as surprised as you.”[13]

Applications

Software cartridge

The VIC-20’s BASIC is compatible with the PET’s, and the Datasette format is the same.[14] Before the computer’s release, a Commodore executive promised that it would have “enough additional documentation to enable an experienced programmer/hobbyist to get inside and let his imagination work”.[15] Compute! favorably contrasted the company’s encouragement of “cottage industry software developers” to Texas Instruments discouraging third-party software.[16] Because of its small memory and low-resolution display compared to some other computers of the time, the VIC-20 was primarily used for educational software and games. However, productivity applications such as home finance programs, spreadsheets, and communication terminal programs were also made for the machine.

The VIC had a sizable library of public domain and freeware software. This software was distributed via online services such as CompuServe, BBSs, as well as offline by mail order and by user groups. Several computer magazines sold on newsstands, such as Compute!, Family Computing, RUN, Ahoy!, and the CBM-produced Commodore Power Play, offered programming tips and type-in programs for the VIC-20.

An estimated 300 commercial titles were available on cartridge and another 500+ were available on tape. Games on cartridge include Gorf, Radar Rat Race, Sargon II Chess, and Jupiter Lander. A handful of disk applications were released.

The VIC’s low cost led to it being used by the Fort Pierce, Florida Utilities Authority to measure the input and output of two of their generators and display the results on monitors throughout the plant. The utility was able to purchase multiple VIC and C64 systems for the cost of one IBM PC Compatible.[17]