Go To: Commodore VIC-20 [24297]

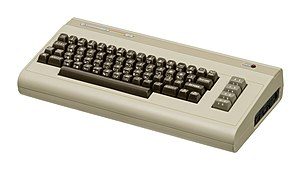

The Commodore 64, also known as the C64 or the CBM 64, is an 8-bit home computer introduced in January 1982 by Commodore International (first shown at the Consumer Electronics Show, in Las Vegas, January 7–10, 1982).[4] It has been listed in the Guinness World Records as the highest-selling single computer model of all time,[5] with independent estimates placing the number sold between 10 and 17 million units.[2] Volume production started in early 1982, marketing in August for US$595 (equivalent to $1,545 in 2018).[6][7] Preceded by the Commodore VIC-20 and Commodore PET, the C64 took its name from its 64 kilobytes (65,536 bytes) of RAM. With support for multicolor sprites and a custom chip for waveform generation, the C64 could create superior visuals and audio compared to systems without such custom hardware.

The C64 dominated the low-end computer market for most of the 1980s.[8] For a substantial period (1983–1986), the C64 had between 30% and 40% share of the US market and two million units sold per year,[9] outselling IBM PC compatibles, Apple computers, and the Atari 8-bit family of computers. Sam Tramiel, a later Atari president and the son of Commodore’s founder, said in a 1989 interview, “When I was at Commodore we were building 400,000 C64s a month for a couple of years.”[10] In the UK market, the C64 faced competition from the BBC Micro and the ZX Spectrum,[11] but the C64 was still one of the two most popular computers in the UK.[12]

Part of the Commodore 64’s success was its sale in regular retail stores instead of only electronics or computer hobbyist specialty stores. Commodore produced many of its parts in-house to control costs, including custom integrated circuit chips from MOS Technology. It has been compared to the Ford Model T automobile for its role in bringing a new technology to middle-class households via creative and affordable mass-production.[13] Approximately 10,000 commercial software titles have been made for the Commodore 64 including development tools, office productivity applications, and video games.[14] C64 emulators allow anyone with a modern computer, or a compatible video game console, to run these programs today. The C64 is also credited with popularizing the computer demoscene and is still used today by some computer hobbyists.[15] In 2011, 17 years after it was taken off the market, research showed that brand recognition for the model was still at 87%.

History

The Commodore 64 startup screen

In January 1981, MOS Technology, Inc., Commodore’s integrated circuit design subsidiary, initiated a project to design the graphic and audio chips for a next generation video game console. Design work for the chips, named MOS Technology VIC-II (Video Integrated Circuit for graphics) and MOS Technology SID (Sound Interface Device for audio), was completed in November 1981.[6] Commodore then began a game console project that would use the new chips—called the Ultimax or the Commodore MAX Machine, engineered by Yash Terakura from Commodore Japan. This project was eventually cancelled after just a few machines were manufactured for the Japanese market.[citation needed] At the same time, Robert “Bob” Russell (system programmer and architect on the VIC-20) and Robert “Bob” Yannes (engineer of the SID) were critical of the current product line-up at Commodore, which was a continuation of the Commodore PET line aimed at business users. With the support of Al Charpentier (engineer of the VIC-II) and Charles Winterble (manager of MOS Technology), they proposed to Commodore CEO Jack Tramiel a true low-cost sequel to the VIC-20. Tramiel dictated that the machine should have 64 KB of random-access memory (RAM). Although 64-Kbit dynamic random-access memory (DRAM) chips cost over US$100 (equivalent to $232.95 in 2018) at the time, he knew that DRAM prices were falling, and would drop to an acceptable level before full production was reached. The team was able to quickly design the computer because, unlike most other home-computer companies, Commodore had its own semiconductor fab to produce test chips; because the fab was not running at full capacity, development costs were part of existing corporate overhead. The chips were complete by November, by which time Charpentier, Winterble, and Tramiel had decided to proceed with the new computer; the latter set a final deadline for the first weekend of January, to coincide with the 1982 Consumer Electronics Show (CES).[6]

The product was code named the VIC-40 as the successor to the popular VIC-20. The team that constructed it consisted of Yash Terakura,[16] Shiraz Shivji,[17] Bob Russell, Bob Yannes and David A. Ziembicki. The design, prototypes, and some sample software were finished in time for the show, after the team had worked tirelessly over both Thanksgiving and Christmas weekends. The machine used the same case, same-sized motherboard, and same Commodore BASIC 2.0 in ROM as the VIC-20. BASIC also served as the user interface shell and was available immediately on startup at the READY prompt. When the product was to be presented, the VIC-40 product was renamed C64. The C64 made an impressive debut at the January 1982 Consumer Electronics Show, as recalled by Production Engineer David A. Ziembicki: “All we saw at our booth were Atari people with their mouths dropping open, saying, ‘How can you do that for $595?'”[6][18] The answer was vertical integration; due to Commodore’s ownership of MOS Technology’s semiconductor fabrication facilities, each C64 had an estimated production cost of US$135.[6]

Market war

1982–1983

Game cartridges for Radar Rat Race and International Soccer

Commodore had a reputation for announcing products that never appeared, so sought to quickly ship the C64. Production began in spring 1982 and volume shipments began in August.[6] The C64 faced a wide range of competing home computers,[19] but with a lower price and more flexible hardware, it quickly outsold many of its competitors. In the United States the greatest competitors were the Atari 8-bit 400, the Atari 800, and the Apple II. The Atari 400 and 800 had been designed to accommodate previously stringent FCC emissions requirements and so were expensive to manufacture. Though similar in specifications, the two computers represented differing design philosophies; as an open architecture system, upgrade capability for the Apple II was granted by internal expansion slots, whereas the C64’s comparatively closed architecture had only a single external ROM cartridge port for bus expansion. However, the Apple II used its expansion slots for interfacing to common peripherals like disk drives, printers, and modems; the C64 had a variety of ports integrated into its motherboard which were used for these purposes, usually leaving the cartridge port free. Commodore’s was not a completely closed system, however; the company had published detailed specifications for most of their models since the PET and VIC-20 days, and the C64 was no exception. Initial C64 sales were nonetheless relatively slow due to a lack of software, reliability issues with early production models, particularly high failure rates of the PLA chip, which used a new production process, and a shortage of 1541 disk drives, which also suffered rather severe reliability issues. During 1983, however, a trickle of software turned into a flood and sales began rapidly climbing, especially with price cuts from $600 to just $300.

Commodore sold the C64 not only through its network of authorized dealers, but also through department stores, discount stores, toy stores and college bookstores. The C64 had a built-in RF modulator and thus could be plugged into any television set. This allowed it (like its predecessor, the VIC-20) to compete directly against video game consoles such as the Atari 2600. Like the Apple IIe, the C64 could also output a composite video signal, avoiding the RF modulator altogether. This allowed the C64 to be plugged into a specialized monitor for a sharper picture. Unlike the IIe, the C64’s NTSC output capability also included separate luminance/chroma signal output equivalent to (and electrically compatible with) S-Video, for connection to the Commodore 1702 monitor, providing even better video quality than a composite signal.

Aggressive pricing of the C64 is considered to have been a major catalyst in the North American video game crash of 1983. In January 1983, Commodore offered a $100 rebate in the United States on the purchase of a C64 to anyone that traded in another video game console or computer.[20] To take advantage of this rebate, some mail-order dealers and retailers offered a Timex Sinclair 1000 for as little as $10 with purchase of a C64. This deal meant that the consumer could send the TS1000 to Commodore, collect the rebate, and pocket the difference; Timex Corporation departed the computer market within a year. Commodore’s tactics soon led to a price war with the major home computer manufacturers. The success of the VIC-20 and C64 contributed significantly to the exit from the field of Texas Instruments and other smaller competitors.

The price war with Texas Instruments was seen as a personal battle for Commodore president Jack Tramiel.[21] Commodore dropped the C64’s list price by $200 within two months after its release.[6] In June 1983 the company lowered the price to $300, and some stores sold the computer for $199. At one point, the company was selling as many C64s as all computers sold by the rest of the industry combined. Meanwhile the TI lost money by selling the 99/4A for $99.[22] TI’s subsequent demise in the home computer industry in October 1983 was seen as revenge for TI’s tactics in the electronic calculator market in the mid-1970s, when Commodore was almost bankrupted by TI.[23]

All four machines had similar memory configurations which were standard in 1982–83: 48 KB for the Apple II+[24] (upgraded within months of C64’s release to 64 KB with the Apple IIe) and 48 KB for the Atari 800.[25] At upwards of $1,200,[26] the Apple II was about twice as expensive, while the Atari 800 cost $899. One key to the C64’s success was Commodore’s aggressive marketing tactics, and they were quick to exploit the relative price/performance divisions between its competitors with a series of television commercials after the C64’s launch in late 1982.[27] The company also published detailed documentation to help developers,[28] while Atari initially kept technical information secret.[29] The C64 was the only non-discontinued, widely available home computer in late 1983, with more than 500,000 sold during the Christmas season;[30] because of production problems in Atari’s supply chain, by the start of 1984 “the Commodore 64 largely has [the low-end] market to itself right now”, The Washington Post reported.[31]

1984–1987

With sales booming and the early reliability issues with the hardware addressed, software for the C64 began to grow in size and ambitiousness during 1984. This growth shifted to the primary focus of most US game developers. The two holdouts were Sierra, who largely skipped over the C64 in favor of Apple and PC compatible machines, and Broderbund, who were heavily invested in educational software and developed primarily around the Apple II. In the North American market, the disk format had become nearly universal while cassette and cartridge-based software all-but disappeared. So most US-developed games by this point grew large enough to require multi-loading.

By 1985, games were an estimated 60 to 70% of Commodore 64 software. The same year, UK-based Gremlin Graphics released the game Monty on the Run, which was noteworthy for marking a turning point in music composition for the SID chip as musician Ron Hubbard discovered a method of “overdriving” the SID to produce music more advanced than the default sound envelopes. The revolution that Hubbard started quickly spread to most European developers, although more conservative American programmers seldom composed SID music with anything other than the default envelopes.[32] At a mid-1984 conference of game developers and experts at Origins Game Fair, Dan Bunten, Sid Meier (“the computer of choice right now”), and a representative of Avalon Hill said that they were developing games for the C64 first as the most promising market.[33] Computer Gaming World stated in January 1985 that companies such as Epyx that survived the video game crash did so because they “jumped on the Commodore bandwagon early.”[34] Over 35% of SSI’s 1986 sales were for the C64, ten points higher than for the Apple II. The C64 was even more important for other companies,[35] which often found that more than half the sales for a title ported to six platforms came from the C64 version.[36] That same year, Computer Gaming World published a survey of ten game publishers that found that they planned to release forty-three Commodore 64 games that year, compared to nineteen for Atari and forty-eight for Apple II,[37] and Alan Miller stated that Accolade developed first for the C64 because “it will sell the most on that system”.[38]

In Europe, the primary competitors to the C64 were British-built computers: the Sinclair ZX Spectrum, the BBC Micro and the Amstrad CPC 464. In the UK, the 48K Spectrum had not only been released a few months ahead of the C64’s early 1983 debut, but it was also selling for £175, less than half the C64’s £399 price. The Spectrum quickly became the market leader and Commodore had an uphill struggle against it in the marketplace. The C64 did however go on to rival the Spectrum in popularity in the latter half of the 1980s. Adjusted to the size of population, the popularity of Commodore 64 was the highest in Finland at roughly 3 units per 100 inhabitants,[39] where it was subsequently marketed as “the Computer of the Republic”.[40]

Rumors spread in late 1983 that Commodore would discontinue the C64.[41] By early 1985 the C64’s price was $149; with an estimated production cost of $35–50, its profitability was still within the industry-standard markup of two to three times.[6] Commodore sold about one million C64s in 1985 and a total of 3.5 million by mid-1986. Although the company reportedly attempted to discontinue the C64 more than once in favor of more expensive computers such as the Commodore 128, demand remained strong.[42][43] In 1986, Commodore introduced the 64C,[44] a redesigned 64, which Compute! saw as evidence that—contrary to C64 owners’ fears that the company would abandon them in favor of the Amiga and 128—”the 64 refuses to die”.[45] Its introduction also meant that Commodore raised the price of the C64 for the first time, which the magazine cited as the end of the home-computer price war.[46] Software sales also remained strong; MicroProse, for example, in 1987 cited the Commodore and IBM PC markets as its top priorities.[47]

1988–1994

By 1988 PC compatibles were the largest and fastest-growing home and entertainment software markets, displacing former leader Commodore.[48] The company was still selling 1 to 1.5 million units worldwide each year of what Computer Chronicles that year called “the Model T of personal computers.”[49] Epyx CEO David Shannon Morse cautioned, however, that “there are no new 64 buyers, or very few. It’s a consistent group that’s not growing… it’s going to shrink as part of our business.”[50] One computer gaming executive stated that the Nintendo Entertainment System’s enormous popularity – seven million sold in 1988, almost as many as the number of C64s sold in its first five years – had stopped the C64’s growth. Trip Hawkins reinforced that sentiment, stating that Nintendo was “the last hurrah of the 8-bit world.”[51]

LucasArts and Microprose put out their final C64 releases in 1988. Epyx and Broderbund supported the C64 through 1989 and EA through 1990. SSI and Origin continued releasing games through 1991.[52]Ultima VI, released in 1991, was the last major C64 game release from a North American developer, and the Simpsons Arcade Game, published by Ultra Games, was the last arcade conversion. The latter was a somewhat uncommon example of a US-developed arcade port as after the early years of the C64, most arcade conversions were produced by UK developers and converted to NTSC and disk format for the US market, American developers instead focusing on more computer-centered game genres such as RPGs and simulations. In the European market, disk software was rarer and cassettes were the most common distribution method; this led to a higher prevalence of arcade titles and smaller, lower budget games that could fit entirely in the computer’s memory without requiring multiloads. European programmers also tended to exploit advanced features of the C64’s hardware more than their US counterparts.

In the United States, demand for 8- and 16-bit computers all but ceased as the 1990s began and PC compatibles completely dominated the computer market. However, the C64 continued to be popular in the UK and other European countries. The machine’s eventual demise was not due to lack of demand or the cost of the C64 itself (still profitable at a retail price point between £44 and £50), but rather because of the cost of producing the disk drive. In March 1994, at CeBIT in Hanover, Germany, Commodore announced that the C64 would be finally discontinued in 1995,[53] noting that the Commodore 1541 cost more than the C64 itself.[53]

However, only one month later in April 1994, the company filed for bankruptcy. It has been widely claimed that between 18 and 22 million C64s were sold worldwide. Company sales records, however, indicate that the total number was about 12.5 million. Based on that figure, the Commodore 64 was still the third most popular computing platform in the 21 century until the Raspberry Pi family replaced it.[54] While only 360,000 C64s were sold in 1982, about 1.3 million were sold in 1983, followed by a major spike in 1984 when 2.6 million were sold. After that, sales held steady at between 1.3 and 1.6 million a year for the remainder of the decade and then dropped off after 1989. North American sales peaked between 1983 and 1985 and gradually tapered off afterwards, while European sales remained quite strong into the early 1990s – much to the embarrassment of Commodore officials who wished to rid themselves of the aging machine.[2]

C64 family

Commodore MAX

Main article: Commodore MAX Machine

Commodore MAX Machine

In 1982, Commodore released the Commodore MAX Machine in Japan. It was called the Ultimax in the United States, and VC-10 in Germany. The MAX was intended to be a game console with limited computing capability, and was based on a very cut-down version of the hardware family later used in the C64. The MAX was discontinued months after its introduction because of poor sales in Japan.[55]

Commodore Educator 64

Main article: Commodore Educator 64

1983 saw Commodore attempt to compete with the Apple II’s hold on the US education market with the Educator 64,[56] essentially a C64 and “greenscale” monochrome monitor in a PET case. Schools preferred the all-in-one metal construction of the PET over the standard C64’s separate components, which could be easily damaged, vandalized or stolen.[57] Schools did not prefer the Educator 64 to the wide range of software and hardware options the Apple IIe was able to offer, and it was produced in limited quantities.[58]

SX-64

Main article: Commodore SX-64

Commodore SX-64

Also in 1983, Commodore released the SX-64, a portable version of the C64. The SX-64 has the distinction of being the first full-color portable computer. While earlier computers using this form factor only incorporate monochrome (“green screen”) displays, the base SX-64 unit features a 5 in (130 mm) color cathode ray tube (CRT) and an integrated 1541 floppy disk drive. Unlike most other C64s, the SX-64 does not have a cassette connector.[59]

Commodore C128

Main article: Commodore 128

Two designers at Commodore, Fred Bowen and Bil Herd, were determined to rectify the problems of the Plus/4. They intended that the eventual successors to the C64—the Commodore 128 and 128D computers (1985)—were to build upon the C64, avoiding the Plus/4’s flaws.[60][61] The successors had many improvements such as a structured BASIC with graphics and sound commands, 80-column display ability, and full CP/M compatibility. The decision to make the Commodore 128 plug compatible with the C64 was made quietly by Bowen and Herd, software and hardware designers respectively, without the knowledge or approval by the management in the post Jack Tramiel era. The designers were careful not to reveal their decision until the project was too far along to be challenged or changed and still make the impending Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in Las Vegas.[60] Upon learning that the C128 was designed to be compatible with the C64, Commodore’s marketing department independently announced that the C128 would be 100% compatible with the C64, thereby raising the bar for C64 support. In a case of malicious compliance, the 128 design was altered to include a separate “64 mode” using a complete C64 environment to try to ensure total compatibility.[citation needed]

Commodore 64C

Commodore 64C with 1541-II floppy disk drive and 1084S monitor displaying television-compatible S-Video

The C64’s designers intended the computer to have a new, wedge-shaped case within a year of release, but the change did not occur.[6] In 1986, Commodore released the 64C computer, which is functionally identical to the original. The exterior design was remodeled in the sleeker style of the Commodore 128.[43] The 64C uses new versions of the SID, VIC and I/O chips being deployed, with the core voltage reduced from 12V to 9V. Models with the C64E board had the graphic symbols printed on the top of the keys, instead of the normal location on the front. The sound chip (SID) was changed to use the MOS 8580 chip. The most significant changes include different behavior in the filters and in the volume control, which result in some music/sound effects sounding differently than intended, and in digitally-sampled audio being almost inaudible, respectively (though both of these can mostly be corrected-for in software). The 64 KB RAM memory went from eight chips to two chips. Basic and the KERNAL went from two separate chips into one 16 KB ROM chip. The PLA chip and some TTL chips were integrated into a DIL 64-pin chip. The “252535-01” PLA integrated the color RAM as well into the same chip. The smaller physical space made it impossible to put in some internal expansions like a floppy-speeder.[62] In the United States, the 64C was often bundled with the third-party GEOS graphical user interface (GUI)-based operating system, as well as the software needed to access Quantum Link. The 1541 drive received a matching face-lift, resulting in the 1541C. Later, a smaller, sleeker 1541-II model was introduced, along with the 800 KB[63] 3.5-inch microfloppy 1581.

Commodore 64 Games System

Main article: Commodore 64 Games System

Commodore 64 Games System “C64GS”

In 1990, the C64 was repackaged in the form of a game console, called the C64 Games System (C64GS), with most external connectivity removed.[64] A simple modification to the 64C’s motherboard was made to allow cartridges to be inserted from above. A modified ROM replaced the BASIC interpreter with a boot screen to inform the user to insert a cartridge. Designed to compete with the Nintendo Entertainment System and the Sega Master System, it suffered from very low sales compared to its rivals. It was another commercial failure for Commodore, and it was never released outside Europe.

Commodore 65

Main article: Commodore 65

In 1990, an advanced successor to the C64, the Commodore 65 (also known as the “C64DX”), was prototyped, but the project was canceled by Commodore’s chairman Irving Gould in 1991. The C65’s specifications were impressive for an 8-bit computer, bringing specs comparable to the 16-bit Apple IIGS. For example, it could display 256 colors on the screen, while OCS based Amigas could only display 64 in HalfBrite mode (32 colors and half-bright transformations). Although no specific reason was given for the C65’s cancellation, it would have competed in the marketplace with Commodore’s lower end Amigas and the Commodore CDTV.

Clones

Clones are computers that imitate C64 functions. In the middle of 2004, after an absence from the marketplace of more than 10 years, PC manufacturer Tulip Computers BV (owners of the Commodore brand since 1997) announced the C64 Direct-to-TV (C64DTV), a joystick-based TV game based on the C64 with 30 video games built into ROM. Designed by Jeri Ellsworth, a self-taught computer designer who had earlier designed the modern C-One C64 implementation, the C64DTV was similar in concept to other mini-consoles based on the Atari 2600 and Intellivision, which had gained modest success earlier in the decade. The product was advertised on QVC in the United States for the 2004 holiday season.[65] By “hacking” the circuit board, it is possible to attach C1541 floppy disk drives, hard drives, second joysticks, and PS/2 keyboards to these units, which gives the DTV devices nearly all the capabilities of a full Commodore 64.[citation needed] The DTV hardware is also used in the mini-console Hummer, sold at RadioShack in mid-2005.

In 2015, a Commodore 64 compatible motherboard was produced by Individual Computers. Dubbed the “C64 Reloaded”, it is a modern redesign of the Commodore 64 motherboard revision 250466 with a few new features.[66] The motherboard itself is designed to be placed in an empty C64 or C64C case already owned by the user. Produced in limited quantities, models of this Commodore 64 “clone” sport either machined or ZIF sockets in which the custom C64 chips would be placed. The board also contains jumpers to accept different revisions of the VIC-II and SID chips, as well as the ability to jumper between the analogue video system modes PAL and NTSC. The motherboard contains several innovations, including selection via the RESTORE key of multiple KERNAL and character ROMs, built-in reset toggle on the power switch, and an S-video socket to replace the original TV modulator. The motherboard is powered by a DC-to-DC converter that uses a single power input of 12 V DC from a mains adapter to power the unit rather than the original and failure prone Commodore 64 power supply brick.